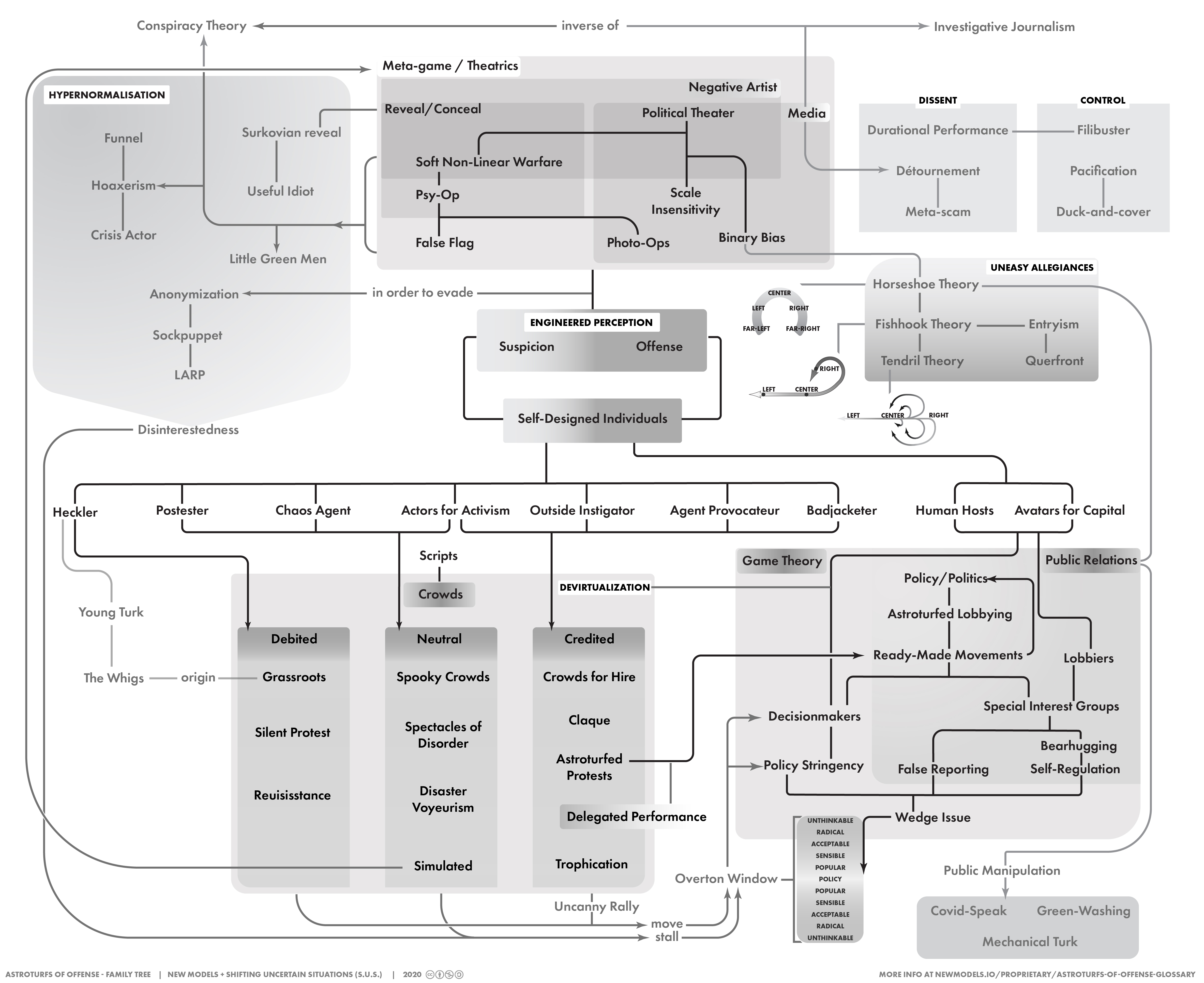

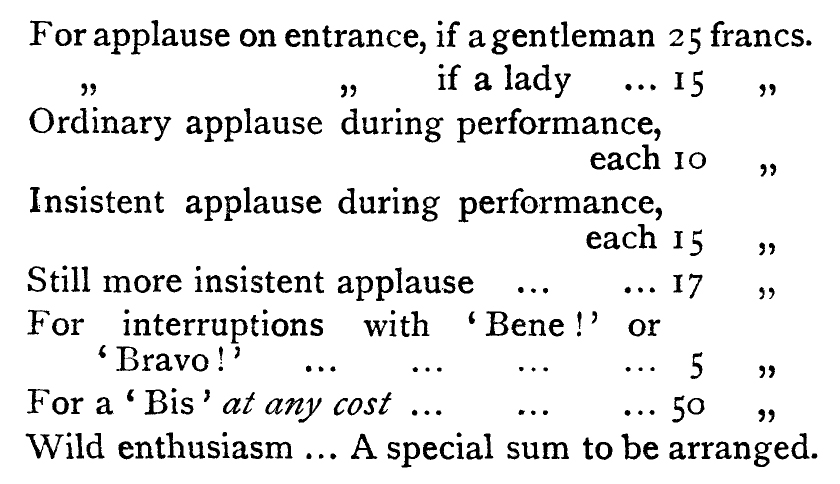

Crowds are groups of people who audience. Audiences are peoples who receive and react to their ever ubiquitously mediatized surroundings.[1] Audiencers themselves are also mediators, between ideas and the material, that act at the nexus of reception and response. Their behaviors are defined and reified into conceptions of public spheres: “laundering device[s]” that “bestow [their] blessing, the indulgence of interest,”[2] producers of “surplus value”[3] in service of shaping locally and globally affective and spectacular opinion. Audiencing exists, and is operationalized in, the field of performative and affective contestation, a force of subjectivity massed together and historically objectified as an instrumentation of influence through the imperceptible normalization of etiquette by power – Roman emperor Nero’s orchestrated claques of bombi, imbrices, and testae.[4]

This imperceptibility of audiencing, the hegemonic insistence and algorithmic necessity of consensus through the audience, has produced an illusion of group authenticity, and, in turn, offense to revelations, glimpses of perceptibility, of external manufacture. Offense that is to “fake crowds,” astroturfed protest, or disingenuous actors who undermine group cohesion;[5] in other words, to the composition of the audience as it has always been, rather than its mirage: an edifice of representation. In obscurity of the audience’s constitution, and in dissonance with an illusion of authenticity that permeates completely to the level of self-designed individuals, the audience and audiencer is held in a state of total suspicion.[6] Civility and motivation, itself defined in the exclusionary violences of defining a public sphere, are evoked in an impossible attempt to deinstrumentalize and narrow the impact of crowds, parsing out and moralizing fictitious good and bad faith individuals in and outside of the crowd. This suspicion exists and circulates upon the safe stages of idea, the loci of, as well as havens from, aesthetic dissemination and agenda setting that provoke audiencers into material action.[7]

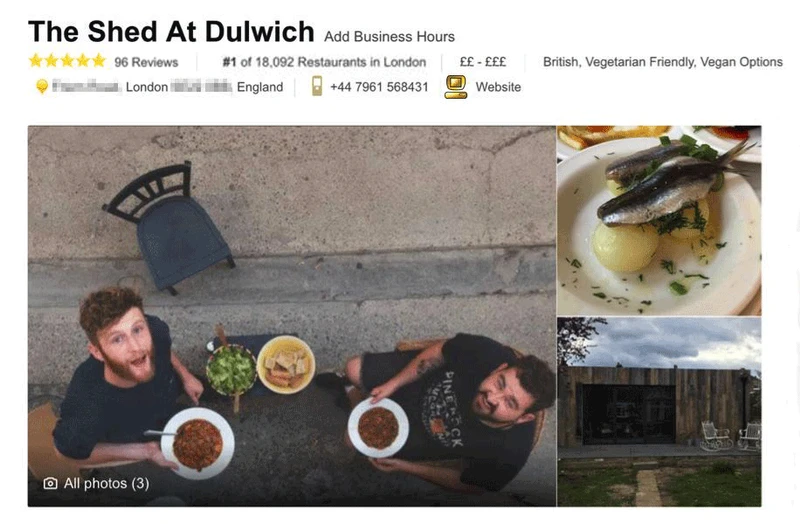

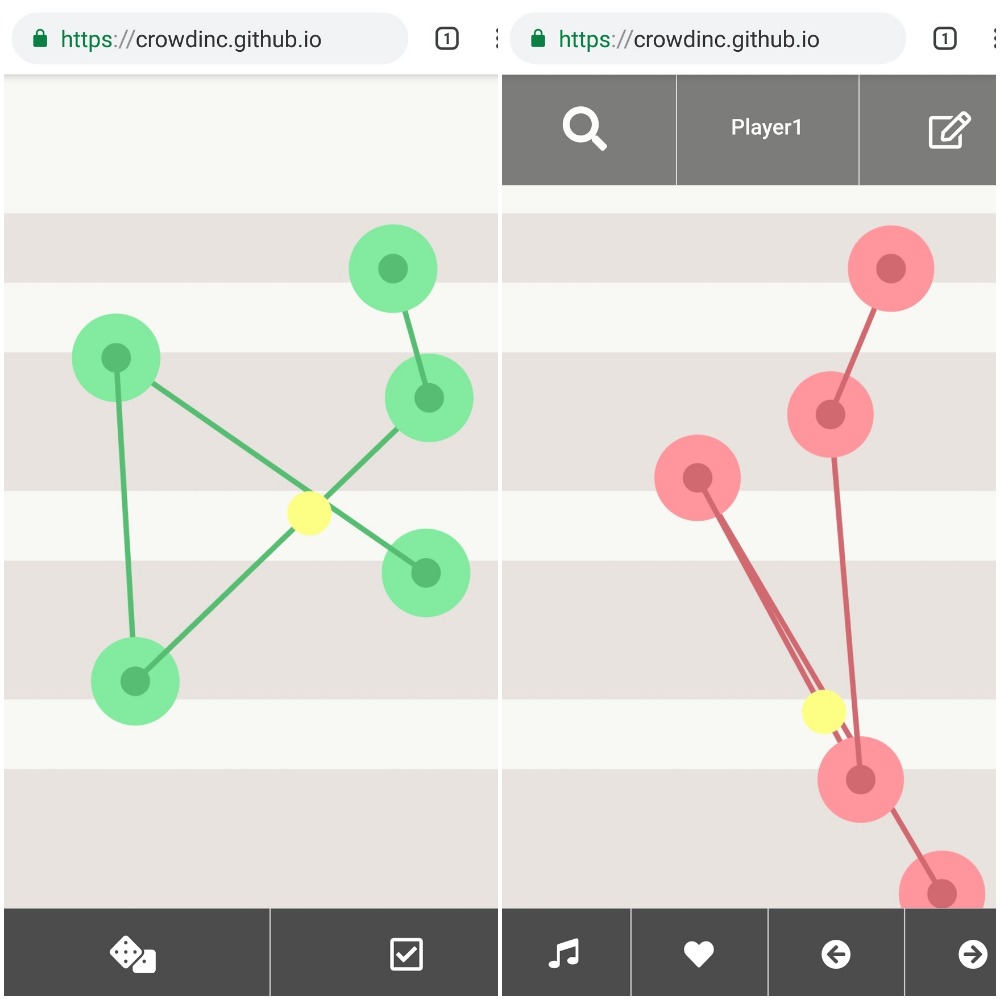

Attempts to reassert the sanctity of a public sphere are an inherently reactionary, ineffectual, and amnesic response to the increasingly visible cracks, fissures, and forthright appropriation of the audience’s legitimating facade.[8] Their effect is rather to produce a nostalgia, itself a dulling and authoritarian gesture, all the meanwhile, unencumbered by the compunction that both power and their reactionary opposition produce, an expanding capture of audiences is occurring and proliferating. For example: beyond the readily evident spectacal of fake crowds, targeted marketing is blinkering audiences with audience engagement applications that track and compel audiencers into individualized, real-time commercial actions.[9]

If these ambitions and further reaching colonization and over-determination of the audience and audiencer are to be countered, if the audience is to be kept from complete capture – a determinantly fixed and sanctified audience cannot be realized – it must take place within the field of performative and affective contestation, by détournements of sorts: exercising and practicing audiencing such that the audience might remain an indeterminate medium through which effecting and alternative sociologies may emerge.

In preparation for these hijackings, this page aims to:

- serve as a reference for historic and contemporary examples where the work of audiencing is explored,

- point towards examples from varied ideological perspectives,

- and be a repository of actions ready to be activated and repurposed.

[1] Seija Ridell and Frauke Zeller, "Mediated Urbanism: Navigating an interdisciplinary Terrain," International Communication Gazette 11 September 2013.

[2] Chris Mann, "'Applause at a feneral'(VI Lenin, What is to be done?)," in L'ecole de la Claque, ONCURATING.org, 2017.

[3] ibid.

[4] Mary Francis Gyles, "Nero: Qualis Artifex?," The Classical Journal.

[5] David Levine, "Some of the People, All of the Time: On the Theory and Practice of Fake Crowds."

[6] Boris Groys, "Self-Design and Aesthetic Responsibility." eflux, June 2009.

[7] Rachel o'Reilly, Nagativity Protocols, in L'ecole de la Claque, ONCURATING.org, 2017.

[8] See for example the question of how to deal with organized antivaccinators in 1897 England: "An Epistolary Claque," The British Medical Journal 20 November 1897.

[9] See for example the RFID attendee/consumer and event tracking businness CrowdSync Technology.